-

Stephen J. Campbell

(author)

-

Turnhout: Brepols ,2020

- Purchase Online

If the fifteenth century in Italy has been seen as the moment when the constellation of disciplines known as “the humanities” begins to take shape, it was also a time when a “crisis in the humanities” – their value, their limits, who and what they included or excluded – was also manifest. A largely nineteenth century construction of “Renaissance humanism” has indelibly cast humanist pursuits in terms of writing, with arts of making or techne sometimes idealized as a second order manifestation of humanist ideas.

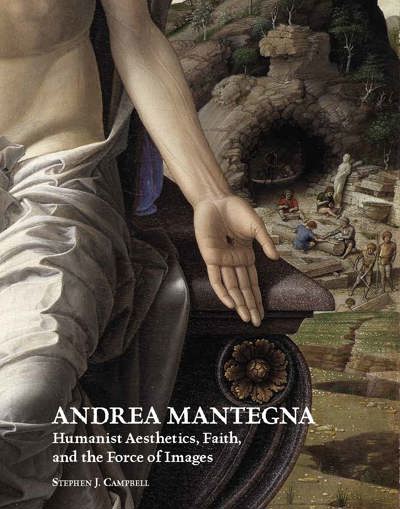

This book re-examines the career of one socially and intellectually ambitious artist, Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506) and his intellectual network, to re-open questions of the locations of humanism, the notion of “humanist art,” or painting as a form of discourse that far from being ancillary to poetry, history, or rhetoric, served as a model for all three. It will be shown that the place of normativity or typicality that Andrea Mantegna occupies in the History of Art – “Early Renaissance artist,” “artist as antiquarian,” “Albertian perspectivist,” has kept from view the more radical potential of his work for a re-description of early Renaissance painting. The major works examined here – the Ovetari Chapel, the Camera Picta, the altarpieces for Padua and Verona, the Triumphs of Caesar, adopt strikingly original means to address their beholder, and to control and even produce their spatial and ideological milieu, challenging conventional notions of “the gaze” and how it operates in early Renaissance art. Furthermore, Mantegna’s representations entail a striking integration of writing and painting as modes of transmission: Mantegna and his audience were highly attentive to the materiality of text, image, and object in the transmission of knowledge. Several of Mantegna works in which architecture or sculpture are depicted (such as The Introduction of the Cult of Cybele to Rome) seem preoccupied by the stability of meaning in the artistic object in circumstances of displacement or commodification. The Triumphs – a monumental series of canvases programmatically devoted to the “bringing back” of the riches of a lost world – offer a programmatic pictorial characterization of what we now call “Renaissance art,” engaging its stylistic desiderata, its technical accomplishments – and, in ways that exceed any theory committed to writing – its ideological implicatedness.

No other artist before him could boast a celebrity like that of Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506), whose career reads like an archetype of Renaissance social ascent. Half a millennium later Mantegna is well-remembered; yet while his importance in any account of a Western Tradition of painting has long been beyond dispute, it has been and remains under-examined and misunderstood. In this provocative re-assessment, based on his Betty Allison Rand lectures at the University of North Carolina 2017, Stephen J. Campbell shows that Mantegna has served the function of illustrating early Renaissance painting, whether the principles of a “humanist theory of art” as prescribed in the De pictura of Alberti, with its elaboration of perspective techniques, or the preoccupation with antiquity and its reconstruction.

While he is rightly regarded a crucial nexus of interaction between the world of the artisan, of the court, and of intellectual life, Mantegna’s importance is still perceived to lie in an early formulation of what is called the “classical tradition,” destined to be surpassed after his death by Raphael and his followers. Campbell argues that the place of normativity or typicality that Mantegna occupies in the History of Art – “Early Renaissance artist,” “artist as antiquarian,” “Albertian perspectivist,” has kept from view the more radical potential of his work for a re-description of early Renaissance painting. In particular, this study of the artist’s major works re-open the questions of “humanist art,” of the relationship between painting and intellectual life, of image-making as a form of discourse that bears a far from passive or ancillary relationship to poetry, history, or rhetoric. Mantegna’s work is shown to challenge and complicate prevailing understandings of the way works of art address their beholders and construct their spatial milieu, of the materiality of painting and the relationship of painting and writing, and the volatile ideologies of classical antiquity as a component of Renaissance painting.